Composite integers with many Euler liars

In [1] we are interested in constructing composite integers

for which the first so many primes are Euler liars. Experimentally we find that

more and more those numbers appear to be Carmichael numbers, and a good way

of treasure hunting is to look at products of Carmichael numbers that themselves

are also Carmichael numbers.

See [2] for all Carmichael numbers up to 1024

that are products of Carmichael numbers. This is exhaustive, while in

[1] the Carmichael products are special ones that are way

larger than 1024.

In [1], Chapter 3, we studied the Euler liar groups for

Carmichael numbers, leading to a classification. See [3]

for the exhaustive classification of the Carmichael numbers up to 1024.

While for Fermat's primality test Carmichael numbers are disastrous, it's nice to see

that for Solovay and Strassen's primality test again Carmichael numbers seem to be

the most obnoxious ones.

The group of Euler liars

In treasure hunting for composite integers for which the first so many primes are

Euler liars it helps to look for composite integers with many Euler liars. Actually

for given composite n the Euler liars form a subgroup 𝓔n

of the multiplicative group ℤn* of integers (mod n).

Let's write I(n) = φ(n) / #𝓔n for

the index of this subgroup in the full group. Clearly we want I(n) to be

small. As there is at least one Euler witness for each composite n we must have

I(n) ≥ 2. In [1], Chapter 3, we proved that

I(n) = 2 for approximately half of the Carmichael numbers, showing why

they are very interesting for our purposes, while the remaining Carmichael numbers have

I(n) = 2m where 2 ≤ m < k, where

k is the number of prime factors of n. We believe the following is true

(see [1], Conjecture 15):

- Open Problem 1: If n is odd and squarefree and I(n) = 2

then n is a Carmichael number.

Sophie Germinus (pseudo)primes

We did a small brute force search for squarefree odd composite integers n <

106 with I(n) = 4, and next to Carmichael numbers we found

only integers of the form n = p(2p-1) where p and 2p-1

both are prime. Primes p such that 2p-1 is also prime have been studied

somewhat, see the OEIS entry [4]. Unlike the very similar Sophie

Germain primes these primes seem to not have been properly named, so (after a suggestion

by Daniel J. Bernstein) we propose the name Sophie Germinus prime for such primes,

and Sophie Germinus pseudoprime for the product p(2p-1) when

p is a Sophie Germinus prime.

In [1], Section 6, we prove that for any Sophie Germinus pseudoprime

n we have I(n) = 4. We believe the following is true

(see [1], Conjecture 15):

- Open Problem 2: If n is odd and squarefree and I(n) = 4

then n is a Carmichael number

or a Sophie Germinus pseudoprime.

The function πSG-(x), counting the Sophie Germinus primes up to x,

conjecturally (see [5]) satisfies

πSG-(x) ~ 2 C2 x / log2x,

where C2 = 0.660161... is the twin prime constant. Asymptotically this is

the same as for the function πSG+(x), counting the Sophie Germain

primes up to x. Just for fun, here is a small table:

| i | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|

| πSG-(10i) | 3 | 8 | 35 | 189 | 1166 | 7752 | 56157 | 423521 | 3306171 | 26571998 | 218134071 | 1822880701 |

|---|

| πSG+(10i) | 3 | 10 | 37 | 190 | 1171 | 7746 | 56032 | 423140 | 3308859 | 26569515 | 218116524 | 1822848478 |

|---|

The number of Sophie Germinus pseudoprimes up to x is (conjecturally)

~ πSG-(√(x/2)) ~ 4 √ 2 C2 (√x) / log2x.

This shows that in the long run they are less abundant than Carmichael numbers,

according to the Erdős conjecture that there are

x1-K(log log log x)/(log log x) Carmichael numbers

below x, for some constant K. In the short run however the situation is

reversed, because at the current bound x = 1024 their number is just

≈ x0.3537, which leads to a (questionable) estimate K

≈ 1.8664. The crossover point where Carmichael numbers start outrunning the

Sophie Germinus pseudoprimes then is at about 10625.6, but this

estimate is highly sensitive for small changes in the estimate for K, so is

very questionable.

Unfortunately (?) for the goal of treasure hunting for composite integers for which

the first so many primes are Euler liars, the Sophie Germinus pseudoprimes seem to

behave far worse than Carmichael numbers. That's why in [1], Section 6,

we call Sophie Germinus pseudoprimes the "next best " option and did not

consider them in earlier sections.

Euler liars for RSA numbers

Any n which is the product of two odd primes we call an RSA number, for

obvious reasons (though here we are not concerned with the RSA cryptosystem). We have

the following result for the number of Euler liars for RSA numbers. This generalizes Lemma 14 in

[1].

- Theorem: For n = p q, where p, q are

distinct odd primes, the number of Euler liars in ℤn* equals

½ d2, where d = gcd(p-1, q-1).

In other words, the Euler liar group index in ℤn* equals

I(n) = 2 φ(n) / d2.

A consequence is the result, announced above, that for Sophie Germinus pseudoprimes, which

have d = p - 1, we have I(n) = 4, and this is best possible,

i.e. I(n) > 4 for all other RSA numbers. On the other side of the spectrum

we have Sophie Germain pseudoprimes and twin pseudoprimes as two examples where

d = 2, so there are only 2 Euler liars in those cases.

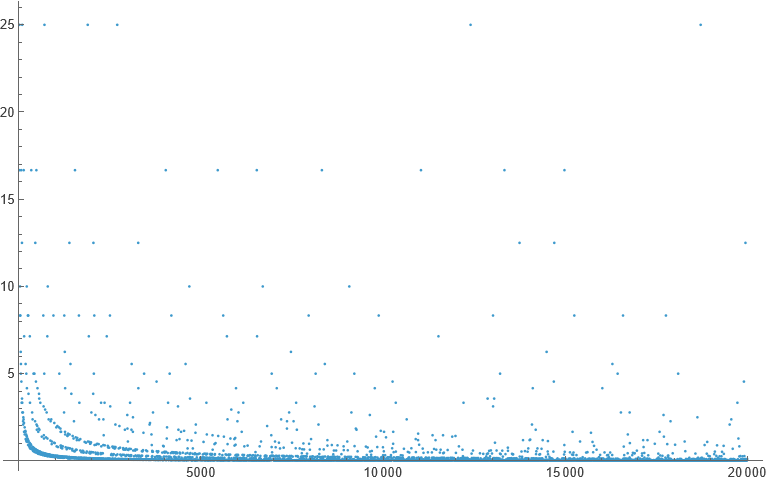

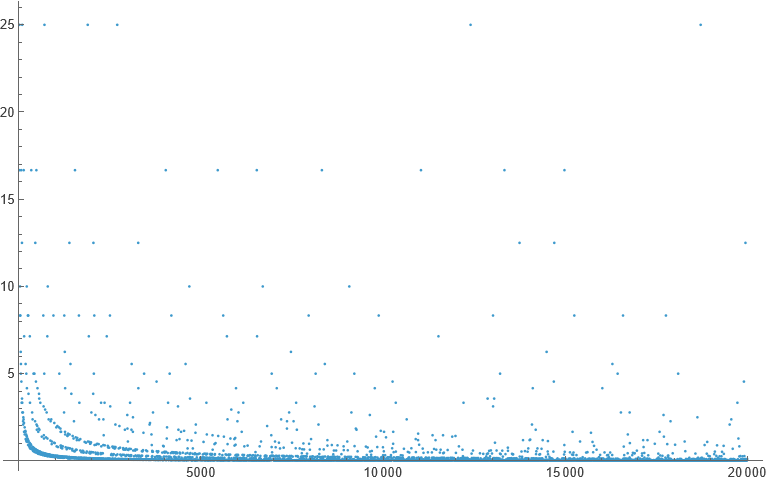

If we take random primes p, q then typically d is small, so the size

of the Eular liars subgroup of RSA numbers n tends to be small. See the figure below,

which shows for the RSA numbers below 20000 the percentage of Euler liars in the full group.

Proof of the Theorem: rsa_eliars.pdf.

Open questions

- What is the (size of the) Euler liars subgroup of ℤn*

for any composite n? The size (or the subgroup index) would make

a nice contribution to OEIS. (For prime n it makes sense to define

I(n) = 1, although the concept of "liar" is a bit weird

in this case.)

- Prove the Open Problems 1 and 2 above. Probably this is within reach.

- Fermat liars also form a subgroup of ℤn* (and a

supergroup of 𝓔n). What can be said about it?

- Strong liars form a subset of Euler liars, in fact, when n ≡

3 (mod 4) the sets are the same. They do not always form a subgroup, when

this happens is known, see [6], Exercise 3.17.

- What about other types of pseudoprimes?

A wealth of information can be found in [7], Chapter 9.

References

[1] Alejandra Alcantarilla Sánchez, Jolijn Cottaar, Tanja Lange,

and Benne de Weger, Ours go to 211: Euler pseudoprimes to 47 prime bases (from

Carmichael numbers), submitted.

[2] Carmichael numbers

that are products of Carmichael numbers.

[3] Classification of

Carmichael numbers.

[4] Primes p such that

2p-1 is also prime, OEIS A005382.

[5] Chris K. Caldwell, An

amazing prime heuristic, arXiv 2103.04483 [math.HO].

[6] Richard Crandall and Carl Pomerance, Prime numbers, a

computational perspective, Second Ed., Springer, 2005.

[7] Eric Bach and Jeffrey Shallit, Algorithmic Number Theory,

MIT Press, 1996.

Authors

Alejandra Alcantarilla Sánchez, Jolijn Cottaar, Tanja Lange, and

Benne de Weger, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands.

January 25, 2026